The new Tora Bora

It may have lost its territory, but its fighters and ideas live on

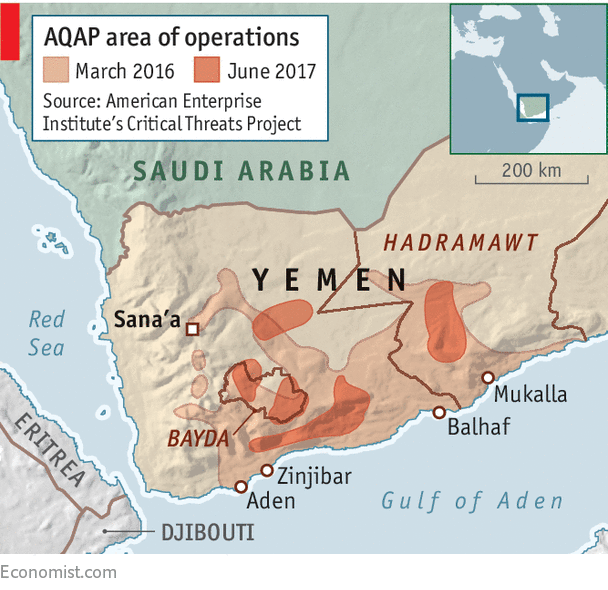

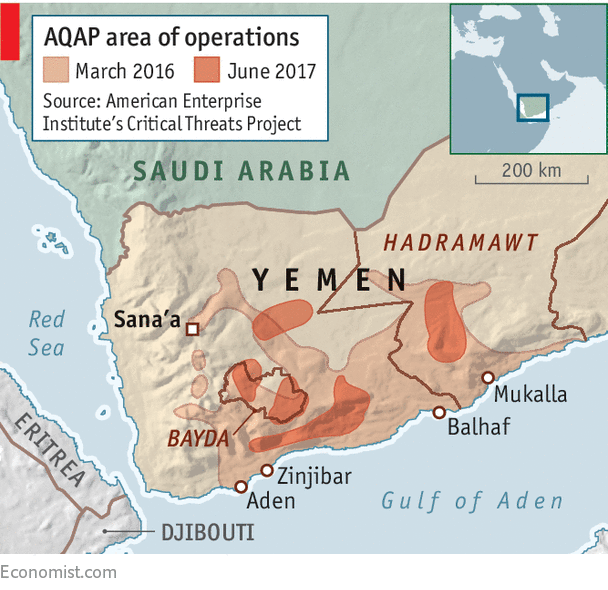

SAFE behind multiple walls of sandbags at his airbase on Yemen’s coast, a United Arab Emirates army commander points at a map of southern Yemen liberally covered in red. It indicates, he says, the reach of al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) in March 2016. A second map, dated six months after his men marched ashore that month, has just a few red blotches left.

In a four-pronged attack, Emirati forces managed in a single day, without loss, to evict AQAP from Mukalla, one of Yemen’s main ports and the capital of its largest province, Hadramawt. Soon after, the Emiratis took Zinjibar, a provincial capital 500km (300 miles) west of Mukalla, and Mansoura, its stronghold in Aden, the main southern port. Security at Yemen’s gas terminal at Balhaf has been reinforced. “If we had not gone in, al-Qaeda would have held the south, and [Shia militias] the north, and Yemen would have been forever off the rails,” says the commander, who is responsible for the UAE’s 5,000-odd soldiers in Yemen. If only beating jihadists everywhere was as easy.

Though AQAP is still seen by some as al-Qaeda’s most potent affiliate, its long arm looks shrivelled today. Its leaders still release videos appealing for lone wolves to strike America and its allies worldwide. But the last foreign attack it claimed, the massacre at Charlie Hebdo, a magazine in Paris, was more than two years ago. Even at its peak, it never looked very professional. Previous attempts to blow up synagogues or America-bound planes with printer-cartridges and booby-trapped underpants were botched. The sum of AQAP’s successful foreign attacks since it was founded in 2009 can be counted on one hand.

The Pentagon says its drones have weakened AQAP. Barack Obama launched around 150 drone attacks on the terror group, wiping out its upper tier, including its best engineers. For the jihadists who survive, getting out of Yemen to kill foreigners has grown harder, thanks to three years of war and the destruction of transport hubs.

Emirati commanders give most of the credit for forcing al-Qaeda to pull back to themselves. Their forces are well-equipped, and they have carefully wooed local support. Before the assault on AQAP in March, the Emiratis paid, armed, kitted and briefly trained 30,000 fighters. Many of AQAP’s recruits were tribal hangers-on, who pragmatically hung up their Kalashnikovs after their leaders ran away from the advancing Emiratis. Whereas Aleppo (in Syria) and Mosul (in Iraq) lie in ruins, Mukalla is almost unscathed.

But AQAP’s retreat might not make it less dangerous. Shorn of territory, it has gone back to being an amorphous and largely invisible network. Hiding in mountain ranges as inaccessible as Afghanistan’s Tora Bora, its leaders still manage over $100m in looted bank deposits, copious heavy weaponry ransacked from military bases, and multiple sleeper cells in cities which can be reactivated at any time. The war has created new opportunities for smuggling and protection rackets, which the jihadists undoubtedly exploit. Demand has also risen for guns for hire.

Few Yemenis would relish al-Qaeda’s return. But given the mayhem now sweeping the south, the order they brought in their year-long rule of Mukalla appeals to some. After taking the port in March 2015, AQAP established a harsh but predictable judicial system. By contrast, their Emirati-backed successors have no courts to try prisoners. The jihadists were not conspicuously corrupt, say locals, with grudging respect. They paid civil servants’ salaries, and were surprisingly flexible in their interpretation of sharia (Islamic law). Men were not forced to grow beards or stop work at prayer time. Male doctors persuaded clerics to let them operate on women, because they lacked female doctors.

UAE commanders now hope to secure Donald Trump’s backing to stay in Yemen until their mission is accomplished. In the first five months of his presidency, Mr Trump has launched more strikes on Yemen than Mr Obama did in all of 2016, including one on the day after he took office. American boots are back on the ground, too, if in small numbers. To speed things up, the White House has eased restrictions on the authorisation of airstrikes.

Despite its success, the campaign against AQAP has critics. Some UAE officers wonder how long it will be before Yemenis view them as occupiers. Another fear is that AQAP’s defeat might create space for Islah, the local offshoot of the Muslim Brotherhood, another Islamist movement against which the UAE is fighting. Instead of breaking al-Qaeda, Yemen’s war could end up spreading it.

This article appeared in the Middle East and Africa section of the print edition under the headline "Yemen’s other war"

http://www.economist.com/news/middle-east-and-africa/21723159-it-may-have-lost-its-territory-its-fighters-and-ideas-live-al-qaeda

It may have lost its territory, but its fighters and ideas live on

SAFE behind multiple walls of sandbags at his airbase on Yemen’s coast, a United Arab Emirates army commander points at a map of southern Yemen liberally covered in red. It indicates, he says, the reach of al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) in March 2016. A second map, dated six months after his men marched ashore that month, has just a few red blotches left.

In a four-pronged attack, Emirati forces managed in a single day, without loss, to evict AQAP from Mukalla, one of Yemen’s main ports and the capital of its largest province, Hadramawt. Soon after, the Emiratis took Zinjibar, a provincial capital 500km (300 miles) west of Mukalla, and Mansoura, its stronghold in Aden, the main southern port. Security at Yemen’s gas terminal at Balhaf has been reinforced. “If we had not gone in, al-Qaeda would have held the south, and [Shia militias] the north, and Yemen would have been forever off the rails,” says the commander, who is responsible for the UAE’s 5,000-odd soldiers in Yemen. If only beating jihadists everywhere was as easy.

Though AQAP is still seen by some as al-Qaeda’s most potent affiliate, its long arm looks shrivelled today. Its leaders still release videos appealing for lone wolves to strike America and its allies worldwide. But the last foreign attack it claimed, the massacre at Charlie Hebdo, a magazine in Paris, was more than two years ago. Even at its peak, it never looked very professional. Previous attempts to blow up synagogues or America-bound planes with printer-cartridges and booby-trapped underpants were botched. The sum of AQAP’s successful foreign attacks since it was founded in 2009 can be counted on one hand.

The Pentagon says its drones have weakened AQAP. Barack Obama launched around 150 drone attacks on the terror group, wiping out its upper tier, including its best engineers. For the jihadists who survive, getting out of Yemen to kill foreigners has grown harder, thanks to three years of war and the destruction of transport hubs.

Emirati commanders give most of the credit for forcing al-Qaeda to pull back to themselves. Their forces are well-equipped, and they have carefully wooed local support. Before the assault on AQAP in March, the Emiratis paid, armed, kitted and briefly trained 30,000 fighters. Many of AQAP’s recruits were tribal hangers-on, who pragmatically hung up their Kalashnikovs after their leaders ran away from the advancing Emiratis. Whereas Aleppo (in Syria) and Mosul (in Iraq) lie in ruins, Mukalla is almost unscathed.

But AQAP’s retreat might not make it less dangerous. Shorn of territory, it has gone back to being an amorphous and largely invisible network. Hiding in mountain ranges as inaccessible as Afghanistan’s Tora Bora, its leaders still manage over $100m in looted bank deposits, copious heavy weaponry ransacked from military bases, and multiple sleeper cells in cities which can be reactivated at any time. The war has created new opportunities for smuggling and protection rackets, which the jihadists undoubtedly exploit. Demand has also risen for guns for hire.

Few Yemenis would relish al-Qaeda’s return. But given the mayhem now sweeping the south, the order they brought in their year-long rule of Mukalla appeals to some. After taking the port in March 2015, AQAP established a harsh but predictable judicial system. By contrast, their Emirati-backed successors have no courts to try prisoners. The jihadists were not conspicuously corrupt, say locals, with grudging respect. They paid civil servants’ salaries, and were surprisingly flexible in their interpretation of sharia (Islamic law). Men were not forced to grow beards or stop work at prayer time. Male doctors persuaded clerics to let them operate on women, because they lacked female doctors.

UAE commanders now hope to secure Donald Trump’s backing to stay in Yemen until their mission is accomplished. In the first five months of his presidency, Mr Trump has launched more strikes on Yemen than Mr Obama did in all of 2016, including one on the day after he took office. American boots are back on the ground, too, if in small numbers. To speed things up, the White House has eased restrictions on the authorisation of airstrikes.

Despite its success, the campaign against AQAP has critics. Some UAE officers wonder how long it will be before Yemenis view them as occupiers. Another fear is that AQAP’s defeat might create space for Islah, the local offshoot of the Muslim Brotherhood, another Islamist movement against which the UAE is fighting. Instead of breaking al-Qaeda, Yemen’s war could end up spreading it.

This article appeared in the Middle East and Africa section of the print edition under the headline "Yemen’s other war"

http://www.economist.com/news/middle-east-and-africa/21723159-it-may-have-lost-its-territory-its-fighters-and-ideas-live-al-qaeda

0 Comments